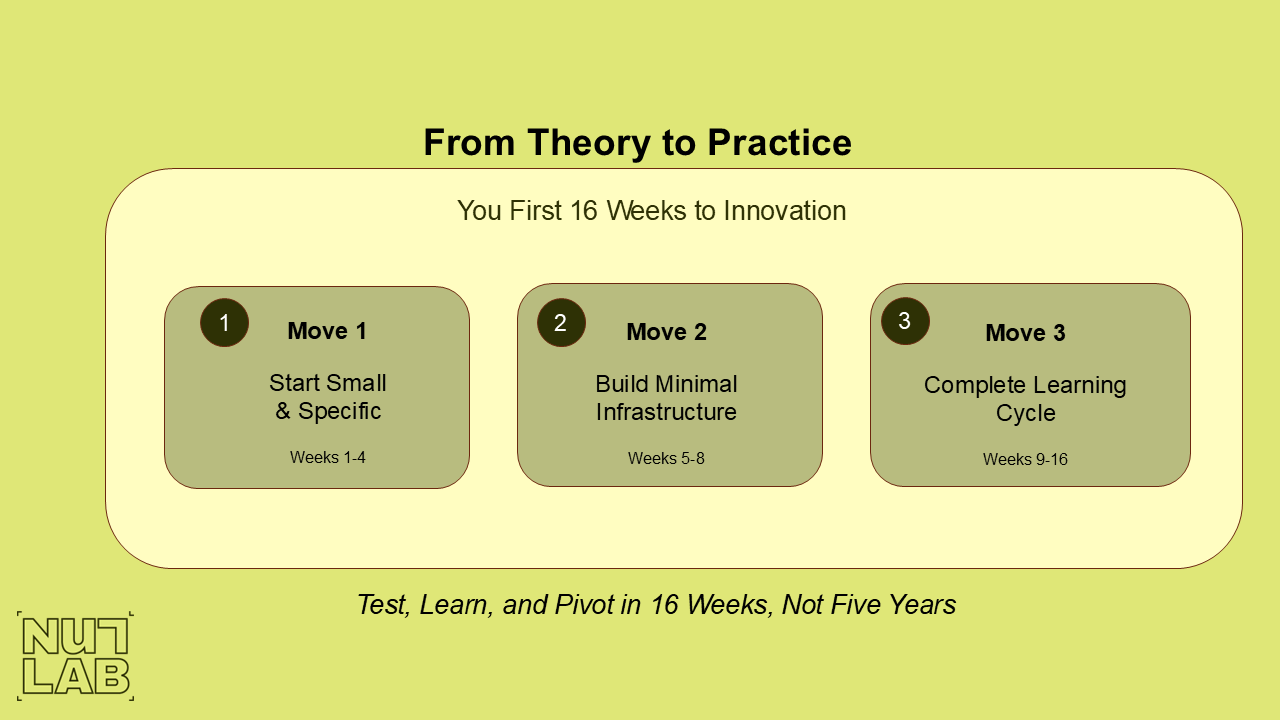

From Theory to Practice: Your 16-Week Roadmap to Innovation

How to Launch Experimental Spaces That Actually Work (No Innovation Theater Required)

You've read about experimental spaces. You understand why they matter. You've probably even convinced leadership that innovation is critical. Now comes the hard part: actually, making it happen.

Here's the uncomfortable truth: most innovation initiatives die not from lack of enthusiasm, but from poor execution. Teams launch with fanfare, stumble through ambiguous mandates, and quietly disband when results don't materialize. The culprit? Trying to do everything at once instead of building momentum systematically.

What follows isn't theory, it's a battle-tested playbook for launching experimental spaces that generate real insights, not just good intentions.

Your First 16 Weeks: Three Strategic Moves

Move 1: Start Small and Specific (Weeks 1-4)

Forget transforming your entire organization overnight. That's innovation theater, not innovation.

Instead, identify one pressing challenge where the old playbook isn't working. Maybe it's a customer pain point that keeps surfacing in feedback. An operational bottleneck that's resisting traditional fixes. Or an emerging market trend that your competitors are capitalizing on while you're still in planning meetings.

Take Spotify's approach: When they noticed playlist discovery was becoming overwhelming for users, they didn't launch a company-wide AI initiative. They formed a small team of 6 people (engineers, designers, and data scientists) to answer one specific question: "How might we help users discover music that matches their mood without requiring active searching?" That focused question led to Spotify's Discover Weekly, which now generates over 40 million personalized playlists every week.

Or consider 3M's Post-it Notes origin story: A small team wasn't tasked with "create a new office product." They were exploring the question: "What can we do with a weak adhesive that failed quality standards?" That narrow, specific inquiry turned a "failed" glue into a $1 billion product line.

Here's what works: Assemble a small, cross-functional team of 5-8 people, no more, no less. Too small and you lack diverse perspectives; too large and you'll drown in coordination overhead.

The critical distinction: Give them a clear question to answer, not a solution to implement. "How might we reduce customer onboarding time by 50%?" beats "Build a new onboarding portal" every time. Questions unlock creativity; predetermined solutions shut it down.

Most importantly, secure explicit permission from leadership to experiment, including permission to fail. When Tata Group launched its "Dare to Try" awards, they didn't just celebrate successes; they specifically recognized teams whose experiments failed but generated valuable insights. The CEO personally presented these awards at company-wide meetings. Within two years, the number of experimental projects across Tata companies increased by 300%. Without air cover from the top, your team will default to safe, incremental improvements that don't challenge assumptions.

Move 2: Create Your Minimum Viable Experimental Infrastructure (Weeks 5-8)

Resist the urge to build a fancy innovation lab before you've proven the concept. What you need is surprisingly modest:

Dedicated time: Even 20% of team capacity is enough to start. One full day per week generates momentum without derailing core responsibilities.

A small discretionary budget: Enough to prototype and test without triggering procurement nightmares. Think hundreds or low thousands, not millions.

Access to customers or end-users: Without real feedback from actual humans, you're just building elaborate guesses.

A simple documentation framework: Notion, Miro, or even a shared Google Doc. The format matters less than the discipline of capturing learnings.

Intuit's "unstructured time" program illustrates this perfectly. They didn't build a separate innovation center. They simply gave developers 10% of their time (about 4 hours per week) and a $500 discretionary budget per project. One engineer used this time to experiment with mobile receipt scanning, an idea that seemed tangential to Intuit's core business. That experiment became SnapTax, which processed over 350,000 tax returns in its first year and fundamentally changed how Intuit thought about mobile-first experiences.

But here's the make-or-break element most organizations overlook: clear guardrails. Your team needs to know exactly what they can test freely versus what requires approval. Ambiguity here kills momentum faster than any bureaucracy.

Amazon's approach is instructive: Jeff Bezos categorized decisions as "one-way doors" (irreversible, requiring careful deliberation) versus "two-way doors" (easily reversible, can be made quickly). Teams can freely experiment with two-way door decisions, launching a limited beta, testing a new feature with 1,000 customers, spending up to $10,000 on prototyping, without executive approval. This framework has enabled Amazon to run thousands of experiments simultaneously while maintaining strategic coherence.

Define the sandbox boundaries explicitly. Can they spend up to $5,000 without approval? Test with 50 customers? Launch a limited beta? Make these decisions upfront, not when your team is stuck waiting for permission that never comes.

Move 3: Run One Complete Learning Cycle (Weeks 9-16)

This is where rubber meets road. Guide your team through the full cycle:

Hypothesis formation: What do we believe is true? What assumptions are we making? What would we need to see to prove ourselves wrong?

Rapid prototyping: Build the smallest version that tests your core hypothesis. Not production ready. Not polished. Just functional enough to generate learning.

Testing with real users: Get your prototype in front of actual customers or stakeholders. Watch what they do, not just what they say. The gap between the two reveals everything.

Synthesis of findings: What did we learn? What surprised us? What assumptions proved wrong? What questions emerged that we hadn't considered?

Airbnb's famous "Obama O's" experiment exemplifies this cycle perfectly. In 2008, struggling with revenue, the founders hypothesized that better photos would increase bookings. Rather than investing in photography infrastructure company-wide, they spent a weekend borrowing a camera and personally visiting New York listings to take better photos. Bookings in those listings doubled. That single experiment, completed in three days for almost no cost, validated an assumption that transformed their business model and led to their professional photography service.

Or look at Dropbox's MVP approach: Instead of building complex file-syncing technology first, founder Drew Houston created a 3-minute video demonstrating how the product would work. He posted it on Hacker News and watched signups jump from 5,000 to 75,000 overnight. The video cost virtually nothing to produce but validated massive demand before writing a single line of production code.

Here's the paradox: The goal isn't a perfect solution. It's demonstrating that disciplined experimentation generates insights that traditional approaches miss. Your first cycle might "fail" in terms of solving the original problem while succeeding brilliantly at teaching your organization how to learn differently.

Consider Procter & Gamble's Febreze story: The product initially bombed in test markets despite eliminating odors effectively. Traditional market research had failed to reveal a critical insight. It wasn't until the team observed how people used air fresheners in their homes that they discovered the problem: people with smelly homes had become nose-blind to the odors. Users weren't looking for odor elimination; they wanted a pleasant scent as a finishing touch to their cleaning routine. That observational learning cycle transformed Febreze from a flop into a billion-dollar brand by repositioning it entirely.

Document everything rigorously. Share learnings broadly, especially the failures. This transparency transforms your first cycle from a team project into an organizational proof of concept.

The Real Test

In 16 weeks, you won't revolutionize your entire organization. But you'll have something more valuable: concrete evidence that structured experimentation works in your specific context, with your actual people, facing your real constraints.

You'll have a team that's learned how to learn differently. Leaders who've seen that encouraging smart risk-taking doesn't lead to chaos. And a repeatable process that can be replicated across other parts of the organization.

The question isn't whether this roadmap is perfect. It's whether you'll start walking it while your competitors are still debating the route.

What's YOUR MOVE to enact an experimental space that generates real insights, not just good intentions?